Stuxnet

Stuxnet was an extremely sophisticated computer worm that exploited multiple previously unknown Windows zero-day vulnerabilities to infect computers and spread. Its purpose was not just to infect PCs but to cause real-world physical effects. Specifically, it targeted centrifuges used to produce the enriched uranium that powers nuclear weapons and reactors.

It's now widely accepted that Stuxnet was created by the U.S. National Security Agency, the CIA, and Israeli intelligence. The classified program to develop the worm was given the code name "Operation Olympic Games"; it was begun under President George W. Bush and continued under President Obama.

While the individual engineers behind Stuxnet haven't been identified, we know that they were very skilled, and that there were a lot of them. Kaspersky Lab's Roel Schouwenberg estimated that it took a team of ten coders two to three years to create the worm in its final form.

Several other worms with infection capabilities similar to Stuxnet, including those dubbed Duqu and Flame, have been identified in the wild, although their purposes are quite different than Stuxnet's. Their similarity to Stuxnet leads experts to believe that they are products of the same development shop, which is apparently still active.

The U.S. and Israeli governments intended Stuxnet as a tool to derail, or at least delay, the Iranian program to develop nuclear weapons. The Bush and Obama administrations believed that if Iran were on the verge of developing atomic weapons, Israel would launch airstrikes against Iranian nuclear facilities in a move that could have set off a regional war.

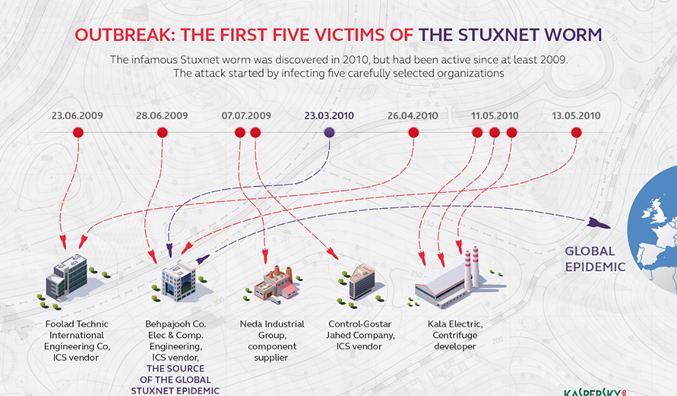

Stuxnet was never intended to spread beyond Iran’s Natanz uranium enrichment. Over time, other groups modified the virus to target facilities including water treatment plants, power plants, and gas lines.

The facility was air-gapped and not connected to the internet. However, the malware did end up on internet-connected computers and began to spread in the wild due to its extremely sophisticated and aggressive nature.

Liam O'Murchu, who is the director of the Security Technology and Response group at Symantec and was on the team that first unraveled Stuxnet says that Stuxnet was "by far the most complex piece of code that we've looked at — in a completely different league from anything we’d ever seen before.” He emphasized that the original source code for the worm, as written by coders working for U.S. and Israeli intelligence, hasn't been released or leaked and can't be extracted from the binaries that are loose in the wild.

However, he explained that a lot about code could be understood from examining the binary in action and reverse-engineering it.

Stuxnet is a computer worm that was originally aimed at Iran’s nuclear facilities and has since mutated and spread to other industrial and energy-producing facilities. The original Stuxnet malware attack targeted the programmable logic controllers (PLCs) used to automate machine processes. It generated a flurry of media attention after it was discovered in 2010 because it was the first known virus to be capable of crippling hardware.

Stuxnet was a multi-part worm that traveled on USB sticks and spread through Microsoft Windows computers. The virus searched each infected PC for signs of Siemens Step 7 software, which industrial computers serving as PLCs use for automating and monitoring electro-mechanical equipment. After finding a PLC computer, the malware attack updated its code over the internet and began sending damage-inducing instructions to the electro-mechanical equipment the PC controlled. At the same time, the virus sent false feedback to the main controller. Anyone monitoring the equipment would have had no indication of a problem until the equipment began to self-destruct.

Although the makers of Stuxnet reportedly programmed it to expire in June 2012, and Siemens issued fixes for its PLC software, the legacy of Stuxnet lives on in other malware attacks based on the original code. These “successors of Stuxnet” included:

Duqu (2011): Based on Stuxnet code, Duqu was designed to log keystrokes and mine data from industrial facilities, presumably to launch a later attack.

A research in 2017 claimed the invisible, fileless malware has gone mainstream and is now found on networks in 40 countries belonging to at least 140 institutions, including banks, government organizations, and telecommunication companies.

Once an infected computer is rebooted, the malware renames itself, making it difficult for digital forensic experts to find any traces of the malware. It was only discovered by a bank’s security team after it found a copy of Meterpreter—an in-memory component of Metasploit—inside the physical memory of a Microsoft domain controller. Researchers found that the Meterpreter code was downloaded and injected into memory using PowerShell commands.

Flame (2012): Flame, like Stuxnet, traveled via USB stick. Flame was sophisticated spyware that recorded Skype conversations, logged keystrokes, and gathered screenshots, among other activities. It targeted government and educational organizations and some private individuals mostly in Iran and other Middle Eastern countries.

Havex (2013): The intention of Havex was to gather information from energy, aviation, defense, and pharmaceutical companies, among others. Havex malware targeted mainly U.S., European, and Canadian organizations.

Industroyer (2016): This targeted power facilities. It’s credited with causing a power outage in the Ukraine in December 2016.

Triton (2017): This targeted the safety systems of a petrochemical plant in the Middle East, raising concerns about the malware maker’s intent to cause physical injury to workers.

Most recent (2017): An unnamed virus with characteristics of Stuxnet reportedly struck unspecified network infrastructure in Iran in October 2018.

While ordinary computer users have little reason to worry about these Stuxnet-based malware attacks, they are clearly a major threat to a range of critical enterprises and industries, including power production, electrical grids, and defense. While extortion is a common goal of virus makers, the Stuxnet family of viruses appears to be more interested in attacking infrastructure. A company cannot easily protect itself from a Stuxnet-related malware attack.